|

|

|

|

This series of profiles of foreign nations is part of the Country Studies Program, formerly the Army Area Handbook Program. The profiles offer brief, summarized information on a country's historical background, geography, society, economy, transportation and telecommunications, government and politics, and national security. Derived from The Library of Congress.

|

|

|

COUNTRY

Formal Name: French Republic (République Française).

Short Form: France.

Term for Citizen(s): Frenchman/Frenchwoman. Adjective: French.

Capital: Paris.

Major Cities: The country’s capital Paris, the only French city with

more than 1 million inhabitants, has a population of 2,142,800 in the

city proper (as of 2004) and 11,330,700 in the metropolitan area (2003 estimate). Greater metropolitan Paris encompasses more than 15 percent of the country’s total population. The second largest city is Marseille, a major Mediterranean seaport, with about 795,600 inhabitants. Other major cities include Lyon, an industrial center in east-central France, with 468,300 inhabitants, and the second largest metropolitan area in France, with 1,665,700 people. Further important cities include: Toulouse, 426,700, a manufacturing and European aviation center in southwestern France; Nice, 339,000, a resort city on the French Riviera; Nantes, 276,200, a seaport and shipbuilding center on the Atlantic coast; Strasbourg, 273,100, the principal French port on the Rhine River and a seat of the European parliament (in addition to Brussels); Montpellier, 244,700, a commercial and manufacturing city in southern France; and Bordeaux, 229,500, a major seaport in southwestern France and the principal exporting center for key French vineyard regions. According to the 1999 decadal census, more than 25 additional French cities had populations surpassing 100,000.

Independence: The French observe July 14, Bastille Day, as their national holiday.

Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Easter Monday (variable date in March or April); Labor Day (May 1); Ascension Day (Thursday, 40 days after Easter); World War II Victory Day (May 8); Bastille Day (July 14); Assumption (August 15); All Saints’ Day (November 1); Armistice Day (November 11); and Christmas Day (December 25).

Flag: The French flag features three equal vertical bands of blue (on the hoist

side), white, and red. Known as the “Le drapeau tricolore” (French Tricolor),

the flag dates to 1790, in the era of the French Revolution.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Pre-modern hominid populations migrated to France during Paleolithic times, and between 30,000 and 10,000 years ago, modern humans left evidence of their presence in cave art. After 600 B.C. Greek and Phoenician traders operated along the French Mediterranean coast, while Celts migrated westward from the Rhine valley, settling the territory later called Gaul by the Romans. The Romans under Julius Caesar conquered part of Gaul in 57–52 B.C., and it remained Roman until the Western Roman Empire disintegrated into small-scale agrarian settlements as the Franks invaded in the fifth century A.D. An interval of territorial consolidation occurred in the eighth century under the Frankish King Charlemagne, who took the title of Holy Roman Emperor. After his death, his three grandsons divided his empire among themselves and held territories corresponding roughly to France, Germany, and Italy. These territories became increasingly feudalized, with rule by numerous local lords. Vikings or “Northmen” raided coastal settlements, colonized Normandy, a territory named after them, and in 1066 conquered England, installing Duke William⎯William the Conqueror⎯as King of England. In the meantime, from 987 and for the next 350 years, an unbroken line of Capetian kings added to their domain, the region surrounding Paris known as the Île-de-France. As royal power gained ground against the feudal lords, the great monastic orders and emerging towns fueled an economic and cultural flowering. By 1328 and the accession of Philip VI, the first of the Valois kings, France boasted the highest achievements of medieval European culture⎯its Romanesque and Gothic architecture⎯and was the most powerful nation in Europe, with a population of 15 million. This population, like others in Europe, suffered a demographic disaster after 1348, when the Black Death (bubonic plague) entered France through Marseille and killed as many as one-third of the country’s inhabitants.

A decade before the Black Death struck, disputed territorial and dynastic claims between France and England led to the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) in France. When the French eventually won, with the help of the young Joan of Arc, the English retained no French possessions except Calais. The Valois dynasty’s holdings came to resemble modern France, once Burgundy and Brittany were added. After the 1540s, the Protestantism of John Calvin spread throughout France and led to civil wars. The Edict of Nantes (1598), issued by Henry IV of the Bourbon dynasty, sustained Catholicism as the established religion of France but granted religious tolerance to the French Protestants (Huguenots) and calmed religious conflict. Absolute monarchy reached its apogee in the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715), the Sun King, who built the Palace of Versailles, a celebration of French art and architecture.

The ambitious projects and military campaigns of Louis and his successors led to chronic financial problems in the eighteenth century. Deteriorating economic conditions and popular resentment against the system of privileges and tax exemptions enjoyed by the nobility and clergy were among the principal causes of the French Revolution (1789–94). The Revolution ended unchecked monarchical rule, enhanced the power of non-noble elites, and brought more equitable land distribution to the peasantry. French revolutionary ideals⎯especially ideals of nationhood and universal rights⎯long proved a powerful influence on the development of national movements elsewhere in the world. However, France’s own first experiment in republican and egalitarian government fell into turmoil, culminating in the “Reign of Terror.” France reverted to forms of dictatorship or constitutional monarchy on four occasions in the nineteenth century⎯the Empire of Napoléon Bonaparte (1804–14, and three-month restoration, 1815), the Bourbon Restoration (1814–30), the reign of Louis-Philippe (1830–48), and the Second Empire of Napoléon III (1852–70). Under Napoléon Bonaparte, France extended its rule and cultural influence over most of Europe before suffering defeat at Waterloo in 1815. Another defeat a half century later, in the Franco-Prussian War (1870), ended the rule of Napoléon III and ushered in the Third Republic, which lasted until France’s military defeat at the hands of Nazi Germany in 1940. Throughout these changes in the political landscape, France remained among the world’s leaders in industrialization, science and technology, and eventually labor and social legislation. France was also a major participant in Europe’s colonial expansion, second only to Britain in the extent of its empire in Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East. Finally, France remained a magnet for generations of avant-garde artists and writers.

Although on the victorious side in World War I, France bore the brunt of the war’s huge human and material losses and emerged at the end of 1918 determined to keep Germany weak through systems of alliances and defenses. Despite these, France was defeated by Nazi Germany early in World War II. In 1940 Nazi troops marched into an undefended Paris, and Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain signed an armistice. France was divided into an occupied north and an unoccupied south, Vichy France, which became a German puppet state with Pétain as its head. Vichy France acquiesced in the plunder of French resources and the deportation of forced labor and Jews to Germany. After four years, Allied armies liberated France in August 1944, and a provisional government was established, headed by General Charles de Gaulle, the wartime leader of Free France. In 1946 de Gaulle resigned, and a new constitution set up the Fourth Republic, featuring a parliamentary form of government controlled by a series of party coalitions. Under this governmental arrangement, France took important steps in promoting international cooperation, when it joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and spearheaded European integration. In 1951, in a dramatic reconciliation, France and Germany, along with four other countries, founded the European Coal and Steel Community. It featured a joint administration, parliament, and supreme court, institutions that still govern today’s European Union (EU). In 1957 France and the same five countries created a broader economic bloc, the European Economic Community, or Common Market, when they acceded to the Treaty of Rome, the core agreement of the EU.

Notwithstanding its accomplishments, the French government was prone to cabinet crises and proved inadequate to the challenge of the independence struggles of the country’s colonies in French Indochina, or present-day Vietnam (1945–54), and Algeria (1954–62). France’s war against communist insurgents in Indochina was abandoned after the defeat of French forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. A revolt in Algeria proved so divisive in France as to threaten a military coup there, prompting the National Assembly in 1958 to invite de Gaulle to return as premier with extraordinary powers. Under the new Gaullist constitution for a Fifth Republic, which strengthened the presidency and reduced legislative power, he was elected president in December 1958. Under de Gaulle, the dissolution of France’s overseas empire continued. The French protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia had received independence in 1956. In 1960 French West Africa was partitioned, and the new nations were granted independence. Algeria, after a long civil war, finally became independent in 1962. Many of the former colonies maintained close economic and cultural ties with France.

In an example of France’s occasionally maverick foreign policy, de Gaulle took France out of the NATO military command in 1967 and expelled all foreign-controlled troops from the country. De Gaulle’s government was weakened by massive protests in May 1968 when student rallies merged with wildcat strikes by millions of factory workers across France. The movement aimed at transforming the authoritarian, elitist French system of governance and came close to forcing de Gaulle from power. After order was reestablished in 1969, de Gaulle resigned and his successor, Georges Pompidou (1969–74), modified Gaullist policies to include a stronger market orientation in domestic economic affairs. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, elected president in 1974, also supported conservative, pro-business policies.

Socialist François Mitterrand was elected president in 1981, beginning a record 14-year tenure in that office. He saw seven prime ministers and two periods of “cohabitation” (1986–88 and 1993–95) in which the prime minister was from the center-right opposition. He also saw France’s first female prime minister, Edith Cresson (1991–92). Early in the Mitterrand presidency, the victorious socialists, carrying out their campaign pledges, imposed a wealth tax, nationalized key industries, decreed a 39-hour workweek and five-week paid vacations, halted nuclear testing, suspended nuclear power plant construction, and abolished the death penalty. The most notable and lasting achievements of the Mitterrand presidency, however, came in the international arena, where France’s major commitment remained the European Economic Community and, especially, improved Franco-German relations, regarded as the key to Europe’s integration. Under Mitterrand, after decades of ups and downs, the Common Market got a boost from the 1986 Single European Act, which eased the free movement of goods and labor. A capstone accomplishment came in the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht, which established a common currency and created the EU to coordinate foreign policy and immigration as well as economics. In promoting the treaty and monetary union, Mitterrand worked well with Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl, strengthening Franco-German economic and security ties.

France continued to be a driving force behind the EU’s progress and expansion under the center-right Gaullist Jacques Chirac, who won the presidency in 1995 on a platform of reducing France’s chronically high unemployment. Chirac briefly resumed France’s nuclear testing in the South Pacific, despite widespread international protests. During his five years of cohabitation (1997–2002) with a socialist legislative majority, the euro was introduced (2002) and the franc retired as legal tender. In 1999 France took part in the NATO airstrikes in Kosovo, despite some internal opposition. In the 2002 presidential election season, Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the neo-fascist, anti-immigrant National Front party, shocked France with his strong performance, a second-place finish in the first round of voting. He took 17 percent of the vote, handing a humiliating defeat to Lionel Jospin, the Socialist prime minister, whose party threw its support behind the incumbent Chirac and bolstered his overwhelming victory of 82 percent in the runoff election. In 2003, in Chirac’s second term, France defied the United States and the United Kingdom in the run-up to the Iraq War by calling for more weapons inspections and diplomacy. France’s stance, although backed by popular sentiment in France, severely strained relations with the United States. In the domestic arena, the Chirac government pressed for unpopular belt-tightening and regulatory reforms of, for example, the pension and wage systems, in order to meet the requirements for monetary union laid out in the Maastricht Treaty. Proposed reforms were greeted each time with protests and street demonstrations across France. Voters also gave Chirac a major setback in May 2005, when they rejected the EU constitution, which he had strongly backed. In November 2005, widespread riots in France’s largely immigrant-origin suburbs expressed a diffuse dissatisfaction and elicited much soul-searching in France about the French approach to immigrant integration and social problems. strongly backed. In November 2005, widespread riots in France’s largely immigrant-origin suburbs expressed a diffuse dissatisfaction and elicited much soul-searching in France about the French approach to immigrant integration and social problems.

GEOGRAPHY GEOGRAPHY

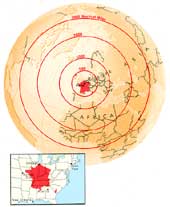

Location: France is composed of its metropolitan territory located Location: France is composed of its metropolitan territory located

in Western Europe and a collection of overseas islands and territories in Western Europe and a collection of overseas islands and territories

located on other continents. The French often refer to metropolitan located on other continents. The French often refer to metropolitan

France as the “Hexagon” because of its shape. Three of the Hexagon’s France as the “Hexagon” because of its shape. Three of the Hexagon’s

six sides are bounded by water—the English Channel and North Sea six sides are bounded by water—the English Channel and North Sea

on the northwest, the Atlantic Ocean and Bay of Biscay on the west, on the northwest, the Atlantic Ocean and Bay of Biscay on the west,

and the Mediterranean Sea on the southeast. The remaining sides, and the Mediterranean Sea on the southeast. The remaining sides,

mostly mountainous, abut Spain and Andorra in the southwest, mostly mountainous, abut Spain and Andorra in the southwest,

Belgium and Luxembourg in the northeast, and Germany, Switzerland, and Italy in the east. The United Kingdom, to the northwest, is now linked to France via the Channel Tunnel, which passes underneath the English Channel. Belgium and Luxembourg in the northeast, and Germany, Switzerland, and Italy in the east. The United Kingdom, to the northwest, is now linked to France via the Channel Tunnel, which passes underneath the English Channel.

Size: The largest West European nation, France has a total area of 547,030 square kilometers (or somewhat smaller than California and New England combined). This area total includes the island of Corsica (8,721 square kilometers) and 1,400 square kilometers of water. Corsica, considered part of metropolitan France, is in the Mediterranean, about 185 kilometers east-southeast of Nice. France’s area total excludes its 10 overseas possessions, mostly remnants of France’s colonial empire. Referred to as “DOM–TOM”—for domaines d'outre-mer and territoires d'outre-mer⎯these possessions include several that are considered to be official departments of France: Guadeloupe and Martinique in the Caribbean, French Guiana in South America, and Réunion in the Indian Ocean. Of these, French Guiana, now used for France’s space launches, is by far the largest, at 91,000 square kilometers.

Land Boundaries: France’s land boundaries total 2,889 kilometers. France borders Belgium (620 kilometers) and Luxembourg (73 kilometers) to the northeast; Germany (451 kilometers), Switzerland (573 kilometers), and Italy (488 kilometers) to the east; and Spain (623 kilometers) and (Andorra 56.6 kilometers) to the southwest. Monaco is completely enclosed by France.

Length of Coastline: France has coastlines along the Atlantic Ocean, the English Channel, and the Mediterranean Sea. These total 3,427 kilometers, including Corsica’s 644 kilometers of coastline.

Maritime Claims: France’s territorial sea extends 12 nautical miles. The continental shelf extends to 200-meter depth or to the depth of exploitation, and the contiguous zone is 24 nautical miles. The exclusive economic (fishing) zone extends 200 nautical miles but does not apply to the Mediterranean. Because of France’s far-flung maritime openings on the world’s oceans, its exclusive economic zone ranks third in the world behind the United States and the United Kingdom.

Topography: France features mostly coastal lowlands, flat plains, and gently rolling hills in the north and west. South-central France has hilly uplands. Mountainous and hilly areas lie on nearly all of France’s borders, creating a series of natural boundaries. Only the nation’s northeastern border is largely exposed. The two principal mountain chains are the Pyrenees, which form the border with Spain, and the Alps, which form most of the border with Switzerland and Italy. The Pyrenees are a formidable barrier because of the absence of low passes and the chain’s elevation—several summits exceed 3,000 meters. The French Alps, at the western end of the European Alpine chain, are also high, with elevations of 3,500 meters, but are broken by several important river valleys, including the Rhône, Isère, and Durance, providing access to Switzerland and Italy. The Jura range on the Swiss border is a lower and less rugged component of the Alpine chain. In the Alps near the Italian and Swiss borders is Western Europe’s highest point—Mont Blanc, at 4,810 meters. The country’s lowest point is the Rhône River delta, at two meters below sea level.

Principal Rivers: Several major rivers⎯extensively navigable⎯drain France, including the Seine, Loire, Garonne, and Rhône. Three of the streams flow west: the Seine into the English Channel; the Loire⎯France’s longest river⎯into the Atlantic; and the Garonne into the Bay of Biscay. The Rhône⎯France’s deepest river⎯flows south into the Mediterranean. For about 161 kilometers, the Rhine constitutes the southern part of the border between France and Germany.

Climate: France’s climate is generally temperate and well suited to agriculture, with major variations: the oceanic and Mediterranean climates. The oceanic climate prevails throughout much of the country, especially in the north and west, where westerly winds from the Atlantic Ocean bring mild and moist conditions. These winds produce cool summers, mild winters with little snow and frost, and year-round rainfall, which usually falls as slow, steady drizzle. Paris, for example, receives 650 millimeters of precipitation annually, with rain occurring an average of 188 days each year. The average daily temperature range in Paris is 1°C to 6°C in January and 13°C to 24°C in July. The Mediterranean climate brings much warmer winters and hot, dry summers along the southern coast.

Natural Resources: France’s most valuable natural asset is its rich agricultural land. High-quality soils cover almost half the country’s surface, giving France an agricultural surplus that makes it an exporter of food. The country’s varied physiography, with beaches, rivers, forests, and mountains, is a draw for the tourism industry. France is not well endowed with indigenous energy supplies or other mineral resources. Hydroelectric production, although well developed, is inadequate to France’s needs.

Land Use: Of France’s land surface, about 33.46 percent is arable and in annually replanted crops, while 2.03 percent is in permanent crops, such as fruit trees and vines. According to a 1998 estimate, an area of about 20,000 square kilometers was irrigated.

Environmental Factors: France faces the usual environmental degradation associated with industrial economies, including air pollution from industrial and vehicle emissions, water pollution from urban wastes and agricultural runoff, soil erosion, acid rain forest damage, and the loss and fragmentation of open space and wildlife habitat. To address these issues, France established the Ministry of the Environment in 1971 and undertook a variety of environmental protection initiatives.

A cornerstone of France’s efforts is to preserve open space and species through the creation of a system of parks and nature reserves. Today, forests and woodlands cover nearly 30 percent of the country, and about 10 percent of the French national territory enjoys some type of protected status. This protected area includes six national parks, several dozen regional nature parks, and more than 100 smaller nature reserves. Successive French governments have also directed environmental efforts against pollution of the air and water. To control its air pollution problem, now mainly caused by transport emissions, the French Environment and Energy Control Agency has developed a monitoring system in accordance with the national Air Pollution Act. The government promotes energy efficiency and emissions reduction with measures to encourage the use of public transportation and cleaner fuels.

Because of such efforts, as well as reliance on nuclear power for most electricity generation, France is closer than other countries to meeting its pledged greenhouse gas emission targets under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. France’s per capita carbon emissions are already the lowest among the major West European countries and declining. Since 1980 the country has cut its energy-related carbon emissions by about 20 percent to 108 million metric tons (2001), somewhat short of its Kyoto target of 102 million metric tons. By 2001 the per capita emissions had declined to 1.83 metric tons of carbon equivalent. In comparison, per capita emissions in 2001 in other large European Union (EU) countries ranged from 2.71 metric tons of carbon equivalent in Germany to 2.05 metric tons in Spain. In 1999 U.S. emissions averaged more than 5 metric tons of carbon per head. In 2000 the French government’s Inter-Ministerial Greenhouse Effect Mission unveiled a 96-point plan for further carbon emission reductions in the 2000–10 period. French measures include a gradually rising carbon tax, which is linked to the 1999 General Tax on Polluting Activities, an ecology tax that will be extended to energy consumption by businesses and electricity producers.

France is also a leader in efforts to prevent marine pollution. As the victim of major oil tanker spills in 1999 and 2002, which were disastrous for the tourism and fishing industries along France’s Atlantic seaboard, France spearheaded more stringent EU regulations on tankers and set in motion constitutional changes in France that would hold polluters financially responsible for damages to fishing, beaches, and wildlife. France, with the support of neighboring countries, also extended its jurisdiction in the Mediterranean from 19 to 145 kilometers, reserving the right to sentence captains of large polluting vessels to fines of up to US$600,000 or four years in prison.

Time Zone: France lies in one time zone, which is one hour ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT+1). The country observes daylight saving time.

SOCIETY

Population: In 2006 the population of France was estimated at 60,876,136, up by more than 2 million since the last census in 1999. In addition, 1.9 million live in France’s overseas departments and territories. The annual population growth rate has averaged about 0.4 percent in recent years, less than half the U.S. rate but somewhat above the low West European norm. Nearly all of the European Union (EU) population growth in recent years has come from France, as in 2003, when France added 211,000 out of the EU’s 216,000 total increase. The population density in France proper is 111 people per square kilometer of land area (2005 estimate). Three-quarters of the French population live in urban settings, defined as cities and towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants.

Demography: Since the late eighteenth century, France’s demographic pattern has differed from that of other West European countries. France was the most populous country in Europe until 1795 and the third most populous in the world, behind only China and India. However, unlike the rest of Europe, France did not experience strong population growth in the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century. The country’s birthrate dropped after the French Revolution, when the peasantry gained an ownership stake in land and then limited births to ensure passing on viable plots of land to their children. Thanks to this limitation, France effected the “demographic transition” to lower birthrates much earlier than other countries, and France’s population eventually fell in comparative terms behind Germany, the United Kingdom, and Italy, as well as a score of non-West European countries. After World War II, France was again atypical among European countries, in that its postwar baby boom lasted longer than elsewhere. As a result, since 1991 France has regained its position behind only Germany as the most populous West European nation. If present trends continue, the French will outnumber the Germans by mid-century.

Estimates on current total fertility rates in France range from very slightly above to slightly below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman. Women continue to postpone childbearing through high contraception usage (legalized in 1967) and abortion (legalized in 1974). In 2004 the average age of women who gave birth was 29.6. Notwithstanding this late childbearing, the native birthrate has been rising slightly and stands at 11.99 per 1,000 (2006 estimate). Infant mortality stands at an extremely low level, 4.2 per 1,000 live births in 2006. The overall death rate is 9.14 deaths per 1,000 population (2006 estimate).

The most striking demographic feature of France, as of other advanced industrial countries, is population aging. France’s median age is 39.1 years. Life expectancy for men and women combined stood at 79.7 in 2006, with men living 76.1 years and women living 83.5 years. Life expectancy gains stem from reductions in adult mortality, with more and more of all deaths occurring in advanced old age. The age structure of the population is typical for Europe, with 18.3 percent under 15 and 16.4 percent over 65, a number expected to grow to 24 percent in 2030. If labor market behavior remains unchanged, France’s labor force will begin to shrink and age significantly after 2010. One person in four of working age will be over 50 in 2010, compared with one in five at the present time.

Positive net migration⎯0.66 migrants per 1,000 in 2006⎯plays a relatively minor role in France’s population dynamics, and, once immigrants are settled in the country, their birthrates fall rather quickly toward the local norm. According to French statistics, this change can occur within a single generation.

Ethnic Groups and Languages: The national language is French, with some rapidly declining regional dialects and languages, including Alsatian, Basque, Breton, Catalan, Corsican, Flemish, and Provençal. French derived from the vernacular Latin spoken by the Romans in Gaul. Historically, French served as the international language of diplomacy, and it remains a unifying force in parts of the world, chiefly, Africa.

France is the most ethnically diverse country of Europe. A crossroads since prehistoric times, the country’s “historic populations” were a blend of European ethnic stocks, Celtic (Gallic and Breton), Aquitanian (related to Basque), Latin, and Germanic. Over the past 200 years, France has been unusual among European states in periodically attracting large-scale immigration. In the nineteenth century, the new populations that arrived⎯forebears of 40 percent of today’s inhabitants⎯included southern Europeans, Belgians, Poles, Armenians, East European and Maghrebi Jews, Maghrebi Arabs and Berbers, sub-Saharan Africans, and Chinese. After World War II, large-scale immigration to France initially came mainly from southern Europe and subsequently from France’s former colonial possessions, especially North Africa. Other ethnic minorities from the French colonial empire⎯apart from North African Muslims⎯are the Indochinese and francophone sub-Saharan Africans.

Among European countries, France has the largest number of people of Muslim origin, perhaps 5–6 million, although some estimate only 2.6 million. The exact number of Muslims of different national origins living in France is not known, because the state does not collect religious or ethnic census data. The Muslim presence in France is of an earlier date than Muslim communities in Germany and the United Kingdom. More than 1 million Muslims immigrated in the 1960s and early 1970s from North Africa, especially Algeria.

France’s last census figures—for 1999—showed 4.33 million foreign nationals living in France, and every year a further 140,000 enter using legal channels, overwhelmingly family reunification. In addition, some 90,000 are believed to enter illegally every year, mainly by overstaying on short-term visas. The government believes there are between 200,000 and 400,000 “sans-papiers”—literally, “paperless ones.” Resisting calls to regularize their situation, the government has recently toughened its stance on immigration, for example, increasing the number of deportations, as well as the number of people refused asylum. In 2006 the government expects to make 26,000 repatriations.

Religion: Between 83 percent and 90 percent of the French population is Roman Catholic, and only 2 percent Protestant. The rate of religious practice among the nominally Catholic population is very low. France also has a Jewish minority of about 1 percent, a Muslim minority of 5–10 percent, and about 4 percent unaffiliated. France’s Muslim population is the largest in Europe.

France lacks official statistics on religion, a fact that reflects the country’s commitment to the religious neutrality of the state, or laïcité, considered necessary for religious freedom. Faced with antidemocratic pressures from the Catholic Church in the early decades of the Third Republic, France promulgated a law in 1905 calling for the strict separation of church and state. The government has since reaffirmed this law, with, for example, a controversial March 2004 bill that banned the display of all conspicuous religious symbols in public schools. This ban targeted in particular the wearing of headscarves by Muslim girls in public schools. The government maintains that the wearing of religious symbols threatens the country’s secular identity, while others contend that the ban on symbols curtails religious freedom.

France currently seeks to encourage the emergence of a “French Islam.” In 2002 the government set up the French Council for the Islamic Faith based on the model of the Consistoire for Jews created in 1808. The government also has called on private divinity schools to train tolerant homegrown imams who can compete with more militant foreign imams. At present, fewer than 20 percent of France’s approximately 1,600 imams have French citizenship, only a third speak French with ease, and half of those who receive regular pay receive it from foreign sources, mainly Algerian, Moroccan, Turkish, and Saudi. Many imams work in unknown “backyard mosques,” a concern for both security agencies and Muslim leaders.

Education and Literacy: France’s literacy rate is 99 percent. The highly centralized state education system is free between ages two and 18 and compulsory for both citizens and non-citizens between ages six and 16. Free preschool and kindergarten for children under age six is widely available. During the school year 2001–2, the percentage of children attending school was 100 percent for ages three to 13, dropping off slightly for ages 14 to 16. Most children in France continue in education beyond age 16. Top students go to high school (lycée) to study for the baccalaureat qualification, while others attend vocational school. Outside the public education system, private education, primarily Roman Catholic, is also available, involving about 20 percent of French pupils.

Every high-school graduate who passes the baccalaureat exam is guaranteed a free⎯or nearly free⎯university education. Higher education in France, which began with the founding of the University of Paris in 1150, now consists of 91 public universities and 175 professional schools, such as the postgraduate Grandes Ecoles, the most competitive and prestigious French universities; technical colleges; and vocational training institutions. University enrollment is high, but only 4 percent of French students make it into the Grandes Ecoles. French higher education, apart from the Grandes Ecoles, is widely considered under-resourced, given the system’s growing enrollments. In 2005 about 25 percent of 21–24 year olds were participating in higher education. About 19 percent complete postsecondary education (by age 34).

Health: The health status of the French population, as reflected in health and mortality indicators, ranks among the best in the industrialized countries. French life expectancy increases more than three months each year, and female life expectancy at birth (83.5 in 2006) was second in the world after Japan. Male life expectancy, at 76.1, is unsatisfactorily low, largely because of excess road accidents and suicide. Infant mortality is just above the very low levels in Scandinavian countries.

As in other developed countries, the principal causes of death are the major noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease (31.1 percent of deaths) and cancer (27.7 percent). Other top causes are accidents (8.3 percent) and diseases of the respiratory system (8.1 percent). In 2005 France reported an adult human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence rate of 0.4 percent and 130,000 people living with HIV. From the beginning of the epidemic through June 2005, authorities reported 60,212 acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) cases and 34,351 AIDS deaths.

The general health of the French population reflects in part the success of the French health system. In 2000 the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a first ever⎯predictably contentious⎯comparative analysis of 191 of the world’s health systems. The WHO ranked the French health care system as the “best health system in the world” (while the U.S. system was ranked 37). The WHO’s assessment was based on five performance indicators: overall level of population health; social disparities in care; health system responsiveness (measured partly by patient satisfaction); distribution of service within the population; and distribution of the health system’s financial burden, including out-of-pocket expenses.

France’s total expenditure on health as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) is 10.1, among the highest rates in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) but significantly lower than the U.S. rate of 16 percent. French spending is higher than other universal systems, such as that of the United Kingdom, which spends an unusually low 6 percent of GDP. France’s per capita expenditure is about US$2,902 (2003).

The French system is a national health insurance (NHI) system, with a public-private mix of hospital and ambulatory care. It provides universal coverage and comprehensive benefits, with the right to health insurance coverage on the basis of residence in France. Providers such as doctors and dentists are free to establish private practices. Patients are free to choose their own providers, usually require no referrals to see specialists, and generally encounter no significant waiting lists for treatment. Health spending is reimbursed generously by the state. At the same time, private insurers are not excluded from the supplementary insurance market. Low-income people receive extra help with their health spending. Given the strengths of the system⎯quality of care, freedom of choice, and equity of access, the French population is relatively satisfied with the health system. However, the recognized strengths come at the price of high and rising costs. Reform efforts to rein in costs, which have shifted costs to the patient through higher out-of-pocket payments, have proven ineffective and raise equity questions.

Welfare: France is among the most successful major countries in limiting disparities of income and wealth and in containing poverty. One factor contributing to this result is a high minimum wage, twice that of the United States. Another factor is the country’s generosity in its provision of many forms of social protection, apart from universal health insurance. In 2003 France’s expenditure on social protection was 30.9 percent of gross domestic product, somewhat above the euro area average of 28.1 percent. The major components of what France calls the national social security system are old-age pensions, health insurance, disability income and worker’s compensation, family allocations, unemployment insurance, survivor benefits, and housing subsidies. A typical low-income working family of four can receive more than US$1,200 a month in various benefits and transfers. The elderly receive the bulk of benefits. Old-age pensions and health care for the elderly consume 70 percent of the public budget for social spending.

Because the population is aging, France faces strong financial pressure to reduce benefits and increase compulsory employer-employee contributions. In adjusting the system, the general proposed direction is to increase means-testing for benefits and to pay for a greater share out of tax revenues rather than employer- and employee-paid social insurance. Such changes in the system would reduce its universality and overall generosity.

ECONOMY

Overview: With a gross domestic product (GDP) in 2006 of US$2,124 billion, France is the sixth largest economy in the world in U.S. dollar terms and the third largest in Europe, after Germany and the United Kingdom (UK). France is a member of the European Union and, as part of the Eurozone, has ceded its monetary policy authority to the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. For the past two decades, the French economy has undergone substantial adjustments that diminished public ownership and planning and increased the sway of markets, especially financial markets, over French business. At its high-water mark in 1985, public ownership accounted for 10 percent of the economy and public-sector employment for 10 percent of employment. By 2000, public-sector employment had been cut in half, and the state’s direct control of the economy was reduced to core areas of public-service provision, such as the post office.

Currently, the French economy, by many measures of economic activity, is thriving. In 2005 productivity measured as GDP per hour worked exceeded that of the United States and the other Group of Seven economies. Large French companies are expanding internationally and performing impressively in the global arena of economics and trade. And France has comparatively low inequality and the lowest poverty rate among the world’s large economies, at 7 percent, compared to 15 percent in the UK and 18 percent in the United States. At the same time, the country is struggling to reconcile its commitment to social equity with the demands of more open European and global markets. The most troubling aspect of the economy is persistently high unemployment⎯between 8 and 10 percent⎯and underemployment. Companies faced with stepped-up international competition have tended to substitute capital for France’s comparatively costly labor. Job creation has failed to keep pace with the number of jobs lost to enterprise downsizing, and many jobs created in the services sector, the most dynamic sector, are inferior to previously available unskilled and semi-skilled jobs. The result in France, as elsewhere, is an economy of insiders and long-term outsiders, where some enjoy secure, well-paid jobs with benefits, while others⎯mostly youth, especially youth of immigrant descent⎯are saddled with insecure, poorly paid work with reduced and diminishing benefits.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): France’s GDP is substantially smaller than that of the United States, Japan, Germany, and China, and slightly smaller than that of the United Kingdom (UK). In 2006 France’s GDP was about US$2,124 billion. Per capita GDP was US$33,894.

The country’s average real GDP growth in recent years, like that of other continental economies, has been relatively lackluster. In 2006 French growth was 1.8 percent, up slightly from 1.5 percent in 2005 but down from 2.3 percent in 2004, a year in which growth in the UK was 3.1 percent. The origins of France’s GDP by sector in 2006 were as follows: agriculture, 2.5 percent; industry and mining, 22 percent; and services, 75 percent (including government services at about 20 percent of GDP).

Government Budget: France’s 2005 revenues totaled US$1,060 billion, while its expenditures totaled US$1,144 billion, including capital expenditures of US$23 billion. The French budget for 2005 lowered the country’s deficit to 2.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), bringing it for the first time in four years back under the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty) cap of 3 percent. Public debt in 2005 was 66.5 percent of GDP. France is not expected to sustain a deficit below 3 percent in 2006 because the economy’s rate of GDP expansion⎯about 1.8 percent⎯and tax receipts are unlikely to offset health care cost increases (which a 2004 reform is expected to slow but not halt). Because of a formal relaxation of European Union rules in 2005, France will likely continue to escape the disciplinary action theoretically envisaged for countries with weak budgetary positions under the European Monetary Union.

Inflation: In 2006 the inflation rate was 1.8 percent, slightly down from 1.9 percent in 2005, a year that also saw a rise in consumer spending of 2.4 percent.

Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing: Endowed with a third of all the agricultural land in the European Union (EU) and a moderate and varied climate, France is the world’s second largest agricultural producer (behind the United States) and the EU’s leading producer. French agricultural production makes up a fourth of the EU total and accounts for 2.5 percent of French gross domestic product (2006 estimate). France has roughly 1 million farms, which benefit substantially from subsidies, especially EU subsidies. Wheat, corn, meat, wine, sugar beets, and dairy products are France’s main agricultural products.

The EU receives 70 percent of France’s agricultural exports. French agricultural exports to the United States, mainly cheese, processed products, and wine, amount to about US$1.75 billion (2003) annually. The United States is the second-largest agricultural exporter to France, with exports⎯largely feeds, seafood, and snack foods⎯totaling US$425 million in 2003.

Several issues related to French agriculture figure in ongoing international debates. One issue is the magnitude of the subsidies that French agriculture receives under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. Some EU states, such as Germany, consider the subsidies disproportionate and an unfair burden on their own resources, while other states, notably the United States, see them as a violation of free trade. Other issues involve France’s insistence on the protection and security of its food supply. France’s food security concerns prompt it to prefer food self-sufficiency (even at the cost of needing subsidies) and to close its doors to products that could pose a threat, such as genetically engineered foods.

France also has forest resources that are among the largest in Europe. The forests⎯about two-thirds deciduous⎯cover almost 17 million hectares and account for a third of the country’s land area. The average figure per capita is 0.3 hectares. Forest cover is growing by about 30,000 hectares, or 0.4 percent a year, through encroachment on former agricultural land. This expansion of forested land partly reflects the continuation of long-existing forest expansion and improvement policies. Since 1947, the government has subsidized the reforestation of 2.1 million hectares of forestland, for a growth of forestland by 35 percent. A quarter of the country’s forests are publicly owned, and 95 percent have free public access. State subsidies, amounting to some 90 million euros per year for the period 2000–9, have been earmarked for assisting communities and private owners to clear and regenerate their forests.

France’s large and growing forestry and wood products sector employs about a quarter of a million people (2000) in some 35,000 companies. The country, which harvests 55 million cubic meters of timber annually, is the largest European producer of hardwood sawnwood and self-sufficient in hardwood raw materials. It is a net importer of softwood sawnwood and pulp for the paper industry. At least half of the pulp consumed in France is recycled material. Trade in forestry products in 2001 amounted to US$2.4 billion in imports and US$1.9 billion in exports.

With maritime openings on all the planet’s oceans, France has the world’s third largest exclusive economic zone, behind the United States and the United Kingdom. In spite of this privileged access to large fishing zones, the northeast Atlantic Ocean remains the fishing zone of most of the French fishing fleet. The production of the French fishing industry is currently growing. In 2006 the catch was as follows: shellfish, mollusks, and cephalopods, 285,291 metric tons, and saltwater fish, 472,914 metric tons. Aquaculture production reached 793,413 metric tons in 2006.

Mining and Minerals: France is not especially rich in natural mineral resources, although the coal deposits of northern France and the iron ore deposits in the east were important in the nation’s early industrialization. The country’s limited iron ore is of poor quality, and the nearly depleted coal reserves are unsuitable for steel production. In 2004 coal mining in France by its state-owned company was phased out altogether in favor of limited imports. Deposits of petroleum and natural gas, small and largely tapped, each yield only 5 percent of France’s consumption. France currently imports iron ore along with most other minerals important in industrial production. France remains a significant producer of uranium, a fuel used in nuclear reactors, and bauxite, from which aluminum is made.

Industry and Manufacturing: France has a large industrial base whose contribution to the country’s economic activity has not diminished in favor of services as dramatically as in other developed countries. French industry still provides 22 percent of jobs, compared to 11 percent in the United States. French industry is highly diversified. Apart from agri-food processing, the key industrial sectors are chemicals and pharmaceuticals, automobiles, metallurgy, telecommunications and electronics, and aircraft. France has been particularly successful in developing dynamic telecommunications, aerospace, and weapons sectors. Toulouse is now Europe’s aviation center.

Energy: France’s total energy consumption in 2001 was 10.5 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu’s), somewhat up compared to a decade previously. The country’s per capita energy consumption⎯178 million Btu’s in 2001⎯is slightly higher than in other West European countries but only about half the level of the United States (342 million Btu’s per capita energy consumption).

Petroleum and nuclear power account for roughly equal fuel shares of France’s total energy consumption⎯at 38 percent and 37 percent of consumption, respectively. With virtually no domestic oil production, France has relied heavily on the development of nuclear power, which now accounts for about 80 percent of the country’s electricity production. The non-petroleum and non-nuclear 25 percent of French energy consumption is divided among natural gas (14 percent), coal (4 percent), and renewables, including hydroelectric (7 percent) and combined geothermal, solar, and wind power (less than 1 percent). France is far behind other European Union (EU) countries, for example, Germany, in meeting the EU target of 20 percent renewable energy by 2010.

France is a net energy importer, with oil imports, chiefly from Saudi Arabia and Norway, accounting for most of the difference between the country’s energy consumption and production. Although France uses only half as much oil per capita as the United States, France is the world’s fifth-greatest net oil importer (behind the United States, Japan, Germany, and South Korea). France also imports more than 95 percent of its natural gas supply, mostly by pipeline from Norway, Russia, Algeria, and the Netherlands. France imports coal for its declining consumption from Australia, the United States, and South Africa.

The French economy was badly shaken by the oil shocks of the early 1970s, being overwhelmingly dependent on imported petroleum supplies. To reduce this dependence, France undertook both energy conservation measures and a crash program to develop its nuclear power industry. France now has more than one-sixth of the world’s total nuclear-based electricity generating capacity, which ranks second in the world (behind the United States). France generates significantly more electricity than it consumes each year and exports the surplus to neighboring countries, mainly to Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany.

Thanks to both moderate per person energy usage and heavy investment in the nuclear alternative, France is the most energy independent Western country. It is also the smallest producer of carbon dioxide among the world’s seven most industrialized countries. France, however, faces a challenge in maintaining its current position, because its nuclear power has weakening public support for both environmental and economic reasons. Environmentalists are concerned about the possibility of accidents and about nuclear waste, which is currently stored on site at reprocessing facilities. Nuclear power may also prove economically unattractive under new EU guidelines, which call for EU-wide competition in electricity markets. Nuclear power in France has hitherto been shielded from such competition, because for many years the state-owned Electricité de France (EdF) supplied electricity in France. The French government is now partially privatizing EdF.

Services: France’s dynamic services sector accounts for an increasingly large share of economic activity (75 percent of gross domestic product in 2006) and has been responsible for nearly all job creation in recent years. The services sector is dominated by financial services, insurance, and tourism.

The banking system, which accounts for 3 percent of GDP, is the third largest private-sector employer in France, with about 500,000 employees. The system has recently seen rapid change through numerous mergers and acquisitions. These gave rise in 2000 to PNB Paribas, which became the largest bank in France and the second largest in the Eurozone in terms of market capitalization. Crédit Agricole ranks second in profits among the top 25 West European banks. Other French banks with global prominence include the recently expanded Société Générale and the recently privatized Crédit Lyonnais. The French insurance sector, which provides nearly 200,000 jobs, was the fifth largest in the world in 2003 and growing, particularly in the life, health, and property insurance classes.

The tourism sector, another major contributor to the French economy, generates 900,000 jobs and a trade surplus of well over US$10 billion yearly. France is the number-one tourist destination in the world, receiving more than 75 million tourists in 2005. The country has more than 17 million tourist beds, including more than 1 million in 40,000 hotels and 16 million in rural lodging, campsites, and youth hostels.

Labor: In 2005 about 28 million people were active in the labor force, for a labor market participation rate about 2 percent below the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average. Between 2000 and 2005, French employment growth averaged 3.1 percent (compared to 3.5 percent in the United States). Workers in France join the workforce later and retire earlier than workers in many other OECD countries. They also work relatively few hours yearly, averaging 37 hours per week (somewhat more than the legally mandated 35 hours per week) with five weeks of paid vacation. At the same time, the worker productivity level measured by output per hour is among the world’s very highest, exceeding the U.S. level.

Except for Scandinavia, France has the world’s highest female labor market participation rate, with women representing about 47 percent of the country’s workforce. This rate, dramatically up over recent decades, reflects in part the structural increase in services-sector employment, which is heavily female, and in part the relative family-friendliness of French workplaces. In the past 20 years, the structure of French employment has shifted toward the services sector⎯now involving more than 70 percent of the workforce⎯away from manufacturing and construction, with about 22 percent, down from 38 percent in 1970. Workers in France receive help in balancing work and family through not only short worktime policies, but also generous subsidies for child care and preschool, sizable child benefits, and up to 26 weeks of paid parental leave, potentially followed by unpaid leave without job forfeiture. Preschool teachers have the equivalent of graduate training in early education and earn wages that are above the average for all employed women. In order to spend an equivalent amount to what France now invests in its family-leave policies and child-care provisions, the United States would have to spend between 1 percent and 1.5 percent of gross domestic product, or about US$115 billion to US$175 billion per year.

The labor code sets minimum standards for working conditions, e.g., the workweek (35 hours), layoffs, overtime, and vacation. It mandates the prorating of benefits between full-time and part-time work. A combination of regulation and collectively bargained agreements gives French workers robust employment protection. Although labor union membership in the private sector is lower than the low U.S. rate, French unions are capable of exerting pressure in political quarters by threatening strikes or resorting to the French tradition of mass mobilization.

France’s employment protection legislation has not hindered the adjustment of French enterprises to their growing exposure to global market competition. French businesses have moved rapidly to streamline their workforces through downsizing and to raise worker productivity through up-skilling and increased capital intensity. The adjustment process, however, has resulted in inadequate job opportunities, particularly for youth. In the last 20 years, the country’s unemployment rate has consistently exceeded 8 percent, hovering around the 10 percent threshold for more than a third of that time. The unemployment problem, according to recent OECD analyses, is not attributable to labor regulation, since France does not differ significantly in the stringency of its labor protection legislation from low unemployment countries such as Austria (2.4 percent), the Netherlands (3.1 percent), Norway (2.3 percent) and Sweden (2.9 percent). Nonetheless, in March 2005 the French government, responding to business groups, passed legislation to give businesses somewhat more flexibility to negotiate overtime pay, vacation times, and workweeks that exceed the 35-hour statutory limit.

Foreign Economic Relations: France was the main driving force behind the economic integration of Europe and remains a powerful force in the European Union (EU). As the member states of Europe’s institutions have grown in number, first to 15 and now to 25, the influence of France has necessarily diminished somewhat. Still, France’s contribution to the EU budget, to directing personnel in the EU, and to shaping the EU’s future is matched or exceeded only by Germany’s. Although the rejection of the EU constitution by the French electorate in 2005 produced some consternation about continuing progress in European integration, the EU’s constitutional basis and France’s central place in the EU remain secure.

Apart from the EU, France plays a major role in many other international economic bodies and regional blocs, including all of the central formal and informal organizations of the industrialized countries, e.g., the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Group of Seven, and numerous regional trade blocs and customs unions in areas where France was formerly active as a colonial power. France, for instance, is a member or plays an advisory role in African economic blocs and organizations, such as the African Development Bank and the Central African States Development Bank. France is one of the world’s most important donors of development aid and loans, whether on a bilateral basis or through multinational agencies, such as the European Development Fund, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

Imports and Exports: The French economy is very open to foreign trade. Total trade⎯imports plus exports of goods and services⎯amounts to about 50 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in France. France is the second-largest trading nation in West Europe (after Germany).

France, the world’s fourth largest exporter of goods and services, sends 70 percent of its trade to European Union partners. Its main customers are Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Spain, along with the United States. In 2005 France’s top-three export destinations were Germany (14.7 percent), Spain (9.6 percent), and Italy (8.7 percent), with the United States receiving 7.2 percent. In 2005 France’s top-three import sources were Germany (18.9 percent), Belgium (10.7 percent), and Italy (8.2 percent), with the United States contributing 5.1 percent. France’s chief exports are machinery and transportation equipment, chemicals, iron and steel products, agricultural products, and textiles and clothing. The chief imports are crude oil, machinery and equipment, chemicals, and agricultural products.

Trade Balance: In 2004, after achieving a positive foreign trade balance for goods for most of the previous decade, France saw a trade deficit, as the euro’s strength damaged trade competitiveness and oil prices surged. Although exports grew in that year, imports grew faster. By 2005, the trade deficit had grown several-fold. In 2005 France’s imports reached US$473.3 billion, while its exports came to only US$443.4 billion, yielding a negative balance of trade of US$29.9 billion. The trade balance is expected to remain in deficit in 2006. The deficit in the sales volume of manufactured goods and lower automobile sales will not be sufficiently offset by the surplus in tourism and exports of services.

Balance of Payments: France’s current account, a broad measure that summarizes the flow of goods, services, income, and transfer payments into and out of the country, fell from surplus into deficit between 2003 and 2004, largely because of deterioration in the visible trade balance. Another factor negatively affecting France’s balance of payments for several years has been a lower surplus on services, which has not been fully offset by a larger surplus on investment income. In addition, as usual, France posted a large deficit on transfers, reflecting its net contribution to the European Union budget and its contribution to international aid. Taken together, in 2005 all of the international interactions yielded a current account deficit of US$38.8 billion, or 1.8 percent of gross domestic product. The deficit more than quadrupled that of 2004.

Foreign Investment: France is among the world’s top destinations for investment by foreigners, whether portfolio investment or foreign direct investment. The formal French investment regime is now among the least restrictive in the world, with no generalized screening of investment by non-French entities. Restrictions on foreign investment in France gradually disappeared in the 1990s. In the 1980s, most acquisitions of a French company by foreign interests were subject to prior approval by the French Ministry of Economy. Since then rules on investment have been liberalized, first for investments by European Union (EU) companies, then for all foreign investments. Only investments involving public security, health, or defense interests are screened. Negative decisions are subject to appeal if they violate the European Community treaty article that guarantees free movement of capital.

Foreigners now hold about 35 percent of the capital of publicly traded French companies. Numerous opportunities for investors, including foreign investors, have been opened up by France’s ongoing privatization process, notwithstanding that privatization legislation gives the French government the option to maintain a “golden share” to “protect national interests.” Foreign-controlled firms play a significant role in France’s economy. They account for 22 percent of the workforce, 27 percent of capital expenditures, 30 percent of exports, and 30 percent of production. Europe is by far the main source of direct investment in France, while the United States is the most active single investor. About 2,000 affiliates of U.S firms are established in France, with about 540,000 jobs resulting from U.S.-origin investments.

A decade of reforms has not entirely overcome the traditional preference for national control of businesses and aversion to foreign investment in the French economy, especially non-EU investment. Labor organizations, for example, sometimes oppose acquisition of French businesses by U.S. firms, on the grounds that U.S. firms focus on short-term profits at the expense of employment and employees. Nonetheless, the French government is committed to providing national treatment to all foreign companies. It provides, for example, equal access to research and development (R&D) subsidies. In 2003 France ranked fourth among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries for research, after Japan, Germany, and the United States, with R&D expenditure of about 2.5 percent of gross domestic product. More than half was financed by the public sector, which operates the major national research centers, as well as numerous centers specialized in particular fields.

Currency and Exchange Rate: As part of the Eurozone, France uses the euro as its unit of currency, having relinquished the franc as legal tender in 2002. The value of the euro has been rising in relation to the dollar. In mid-April 2007, the exchange rate was 0.74 euros=US$1.

Fiscal Year: France’s fiscal year is the calendar year.

TRANSPORTATION AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS

Overview: France has a high-quality transport infrastructure in which road, rail, air, and water transport all play a significant role. The land transport infrastructure is among the best in the world and continues to improve. The closing decades of the twentieth century saw the development of high-speed train services (trains à grande vitesse—TGVs) and further expansion of the national network of limited access highways. French telecommunications are also among the world’s best.

Roads: The French road network is the densest in the world and the longest in the European Union with a total of about 985,000 kilometers of local, secondary, and main surfaced roads. This figure includes more than 10,000 kilometers of controlled-access divided highways, which gives France the second most extensive superhighway network in Europe. With a traffic density of 30 vehicles per kilometer, the French highway network is well below the European average of 44 vehicles per kilometer. This below-average traffic density facilitates the delivery of freight, 73 percent of which is carried by road in France.

Railroads: France’s railroad system has a total of about 32,000 kilometers of track, including 167 kilometers of narrow (1 meter) gauge. Annual rail traffic in France comprises 315 million passengers on the main network, 560 million on the regional network around Paris, and 83 million on the high-speed train network. In 2003 the French rail system handled about 126 million metric tons of freight.

With its high-speed trains (trains à grande vitesse—TGVs), France holds the world land speed record—set in 2007—of 574.8 kilometers per hour. The TGV, mainly a passenger train, runs on about 1,500 kilometers of special track, traveling in normal commerical operation at 270 kilometers an hour. The TGV connects cities in France, especially Paris, and in adjacent countries, including Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland. The first high-speed line opened in 1981 from Lyon to the outskirts of Paris. The TGV network grew through the 1990s, with extensions to Brussels, the introduction of the Eurostar service to London through the Channel Tunnel, and the extension of the TGV–Méditerranée track from Valence to Marseille, which entailed the construction of viaducts and extensive railroad cuttings. Opened in 2001, the latter extension reduced the travel time between Marseille and Paris to just three hours. For the sake of cost savings, much of the future development of high-speed services will involve the use of existing track and specially designed tilting trains.

In 1997, to promote greater efficiency across the French rail network, the French National Railroad Company which operates it, the Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Français (SNCF), was reorganized, and the management of its track and related infrastructure was transferred to a new entity, the Réseau Ferré de France (RFF). When European Union–wide rail freight deregulation became effective in 2003, the RFF was obliged to open its track to freight operators other than the SNCF. Rail freight traffic as a proportion of France’s total freight traffic has declined considerably over the past two decades, and this part of the SNCF’s business has been operating at a loss.

Ports: Five of Europe’s 15 busiest ports are located in France: the autonomous maritime ports (owned by the state) of Marseille, Le Havre, Dunkirk, St. Nazaire, and Bordeaux. These five ports, along with France’s other autonomous ports of Rouen, Nantes, and Guadeloupe, control large port areas and handle 80 percent of the goods traffic through ports, more than 345 million metric tons of merchandise a year, half of all foreign trade. Some two dozen other ports, declared national ports for their significance, see 80 percent of all passenger port traffic.

Marseille is the largest French and Mediterranean port and the third largest in Europe in freight traffic, handling 95.5 million metric tons of cargo in 2002. Le Havre is France’s largest container port and Europe’s fifth ranked. Dunkirk, which handles 47.56 million metric tons annually, is growing in part because of cross-channel traffic. It is followed in tonnage by St. Nazaire, with 31.7 million metric tons, and Bordeaux, with 8.96 million metric tons.

French ports are international dispatching points with highly developed intermodal transport connections. The Compagnie Nouvelle de Conteneurs (CNC) ensures that sea freight from the main French ports is distributed daily throughout the country. The “Quality Net” European Network, with its hub in the French city of Metz, links the main French ports with surrounding European countries.

Inland Waterways: France has a system of large, navigable rivers, such as the Loire, Seine, and Rhône, that crisscross the country and, supplemented by connecting canals, have long been essential for trade and travel. The country has about 15,000 kilometers of waterways, 8,500 kilometers of which are heavily traveled. In 2001 the waterways transported more than 56 million metric tons of freight. The autonomous Port of Paris has become the leading river port in France and the second busiest in Europe, handling 20.3 million metric tons of merchandise. Le Havre, located on the Seine River estuary, is an important river as well as maritime port. Rouen is the largest port in Europe for grain export. Over the last few years, major operators of waterway transportation have worked to enhance its reliability and capacity to handle large volumes of cargo.

Civil Aviation and Airports: Because of its numerous urban and industrial centers, France has a particularly high number of airports. Of its 878 airports and airfields, 801 are paved, including 476 with runways more than 3,047 meters long. Three airports handle most of France’s international passenger and cargo service, including Paris’s two main airports, Orly to the south of Paris and Roissy–Charles de Gaulle to the northeast of Paris (with its own rail station on the high-speed train interconnection). The third international airport is Nice–Côte d’Azur. Other regional airports, notably Lyon’s Saint-Exupéry (also with its own high-speed train station), have sought to expand their international services.

Through its international airports, France handles 6,200 flights every week. The two Paris airports handle 20 percent of the total airfreight in the European Union (EU). Their annual traffic growth of more than 10 percent greatly exceeds the 2 to 3 percent growth of most other European airports.

About 900 aircraft, including helicopters, operate under the French flag. The national carrier, Air France, was partly privatized in early 1999 and has recently operated in an environment of EU-wide deregulation. The location of the European Airbus project in Toulouse has turned the city into the European aviation center.

Pipelines: France’s pipeline system carries crude oil over 3,059 kilometers of pipeline, petroleum products over 4,487 kilometers, and natural gas over 24,746 kilometers.

Telecommunications: The French telephone system, with some 39,200,000 telephones, is highly developed, relying for domestic traffic on extensive cable and microwave radio-relay networks, widely introduced fiber-optic systems, and satellite systems. The international system relies on two Intelsat earth stations (with a total of five antennas⎯two for the Indian Ocean and three for the Atlantic Ocean), high-frequency (HF) radio communications with more than 20 countries, Inmarsat service, and Eutelsat TV service.

Until 1997, the state-owned France Télécom had a monopoly on telecommunications in France In 1997 the government began reducing its stake, now below 42 percent. While the partially privatized France Télécom maintains its monopoly on local calls, the telecommunications sector has been opened to competition in the European Union (EU)–wide deregulated market, and other companies offer telephone subscriptions for long-distance and medium-distance calls.

France Télécom, acquiring the British company Orange, secured its leading position in the highly competitive domestic mobile phone market. At the same time, acquisitions made France Télécom the world’s most highly indebted company, requiring a rescue plan in late 2002. The financial future of the company as well as of the entire sector in France and EU-wide, is uncertain. Since the late 1990s, mobile phone subscriptions have risen sharply, but so has investment. At the end of 2001, 59.4 percent of the French population subscribed to a mobile phone service. Operating licenses for third-generation mobile phones, using Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) technology, have been awarded to France Télécom, Cegetel, and Bouygues.

In Internet use, France is catching up to the world’s leaders, after a slight lag. At the end of 2001, 31.9 percent of the French population—almost 19 million people—had Internet access, compared with 61.8 percent in the United States, 40.2 percent in the United Kingdom, and 37.7 percent in Germany. Among the French with secondary education and above, the level is much higher. By late 2003, 93 percent of companies had Internet connections, and 56 percent had their own Web sites. There are a few thousand French-owned online shopping sites, but French consumers have shown limited enthusiasm for e-commerce.

Index for France:

Overview | Government